By Marc Kaufman

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

HAT CREEK, CALIF. -- The wide dishes, 20 feet across and raised high on their pedestals, creaked and groaned as the winds from an approaching snowstorm pushed into this highland valley. Forty-two in all, the radio telescopes laid out in view of some of California's tallest mountains look otherworldly, and now their sounds conjured up visions of deep-space denizens as well.

The instruments, the initial phase of the planned 350-dish Allen Telescope Array, are designed to systematically scan the skies for radio signals sent by advanced civilizations from distant star systems and planets. Fifty years after it began -- and 18 years since Congress voted to strip taxpayer money from the effort -- the nation's search for extraterrestrial intelligence is alive and growing.

"I think there's been a real sea change in how the public views life in the universe and the search for intelligent life," said Jill Tarter, a founder of the nonprofit SETI Institute and the person on whom Carl Sagan's book "Contact," and the movie that followed, were loosely based.

"We're finding new extra-solar planets every week," she said. "We now know microbes can live in extreme environments on Earth thought to be impossible for life not very long ago, and so many more things seem possible in terms of life beyond Earth."

The Hat Creek array, which began operation two years ago, is a joint project of the SETI Institute and the nearby radio astronomy laboratory of the University of California at Berkeley. Made possible by an almost $25 million donation from Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, the array is unique and on the cutting edge of radio astronomy. SETI and Berkeley share both the facility, 290 miles northeast of San Francisco, and all the data it collects.

The dishes also represent a coming-of-age for SETI Institute enthusiasts and its sometimes hailed, sometimes ridiculed mission. While their effort was long associated with UFOs, over-excited researchers and little green men, it is now broadly embraced as important and rigorous science, and astronomers and astrobiologists in an increasing number of nations have become involved in parallel efforts.

"This is legitimate science, and there's a great deal of public interest in it," said Alan Stern, a former assistant administrator at NASA who, in 2007, decided that proposals for extraterrestrial search programs should not be banned from the agency, as they had been since the early 1990s. The National Science Foundation had come to a similar decision a few years before.

"It was not a big or difficult decision to change the policy," said Stern, who invited Tarter in to describe her program to NASA officials. "The technology and science had advanced, and so it made no sense to block applications."

Limited search programs for intelligent extraterrestrials in the 1970s and 1980s abruptly lost their federal funding in 1992, after NASA proposed a greater effort. Former Sen. Richard Bryan (D-Nev.) led the charge in Congress, telling the Senate at one point: "The Great Martian Chase may finally come to an end. As of today, millions have been spent and we have yet to bag a single little green fellow. Not a single Martian has said, 'Take me to your leader,' and not a single flying saucer has applied for FAA approval."

The funding was eliminated, even though SETI listens for radio signals from distant planets and has nothing to do with Mars or with a supposed search for flying saucers or other space oddities.

But when NASA informed Congress that it was going to allow SETI to once again compete for funds, there were no objections, Stern said. Rita Colwell, who was director of the National Science Foundation when it approved a small-scale SETI Institute proposal in 2004, said several prominent astronomers endorsed the group, saying that the institute had become an important player in the field of radio astronomy.

Still, search activity by the institute and others is often criticized for its lack of results. It has been 50 years since astronomer Frank Drake first used a radio antenna at the Green Bank National Radio Astronomy Observatory in West Virginia to listen for extraterrestrial signals, and so far no messages have been detected and confirmed. UCLA physicist and astronomer Ben Zuckerman often lectures on what he considers the overly optimistic predictions of search advocates, and he argues that if the Milky Way were home to technologically advanced civilizations we would know it by now. "I think very strong arguments can be brought to bear that the number of technological civilizations in the galaxy is one -- us," he said.

Although disappointing to scientists searching for intelligent life beyond Earth, the absence of contact is something they consider far from surprising. As Tarter described the effort, the number of star systems studied so far for possible communications is minuscule compared with the number of stars in the sky -- on the same scale as if a person searched for a fish in the Earth's combined oceans by drawing out a single cup of water.

"The chances of finding a fish in that one cup are obviously very small," she said. As she and others often point out, astronomers think the universe contains something on the order of 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars and, given the discovery so far of more than 400 extra-solar planets, it is generally assumed that billions or trillions more are orbiting in distant systems.

What's more, it remains far from certain that listening for radio signals is the right approach. Radio is a relatively primitive form of communication, and advanced civilizations could be sending signals in many different ways. Given that possibility, astronomers have begun using optical telescopes to search for nanosecond laser blips and beeps that might be coming our way.

A Harvard-Princeton University collaboration has resulted in some of the most sophisticated optical searches, and the effort now has worldwide appeal. In November, for instance, a group of 30 optical and radio observatories and amateur astronomers dedicated two nights to simultaneously viewing one particular star system in search of radio signals or laser pulses. The effort, led by Shin-ya Narusawa of the Nishi-Harima Observatory in southern Japan, targeted a system described in 1993 by Sagan and Paul Horowitz (leader of the optical search team at Harvard) as potentially habitable.

"In Japan, our telescopes are all open to the regular people, and when they come in we want to know what are their big interests in astronomy," Narusawa said during the nighttime observation. "The top two are these: Is there an end, a border, to the universe? And is there life, especially intelligent life, anywhere other than Earth?"

Narusawa said he hoped to cooperate with the SETI Institute in the future, as well as with more fledgling SETI programs in South Korea and Australia. Drake, the man who first began listening for intergalactic signals in 1960 and chairman emeritus of the SETI Institute's board, remains engaged in the search. When different channels, sensitivities and computing power are factored in, the technology now being brought to the effort is 100 trillion times more powerful than what he started with, Drake said. The explosion of radio "noise" from high-definition television, cellphones and military satellite communication makes it more difficult to identify a true signal from elsewhere, but ever more powerful computers are being used to read the data coming in.

In addition to his work in institutionalizing the search effort and broadening the SETI Institute's mission to include more traditional astronomy, Drake is known for the "Drake Equation," an effort to quantify how likely it is that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe.

The equation has been firmed up somewhat in recent years as a scientific consensus has grown that extra-solar planets are commonplace in other solar systems, but it remains essentially speculative since it relies on estimates of the likelihood of life's beginning and evolving on seemingly habitable planets. However, the equation could become more precise in the years ahead if NASA's Kepler mission, launched last year, finds the Earth-size planets it is designed to detect (and which many astronomers believe are prevalent in the Milky Way and other galaxies).

Based on the Drake Equation, there should be an intelligent civilization orbiting one in 10 million stars. Although that is a tiny fraction, it is nonetheless a lot of potential intelligent extraterrestrials given the vastness of the universe; the Milky Way alone is believed to have more than 100 billion stars. That fraction also explains why SETI pioneers such as Drake are not surprised that no signals have been detected so far.

"We've looked at far, far fewer than 10 million stars since 1960, and so we really can't say anything worthwhile yet about whether or not intelligent life is out there," Drake said. "Given our capabilities now, we might have something useful to say one way or another in 25 years."

That's not the kind of time scale generally used in science programs, but SETI is hardly a typical scientific effort. Drake, who is nearly 80 years old, says he doubts he will be around when a signal is detected, but he is more than pleased with what his initial two-month effort in 1960 (named Project Ozma) has spawned.

Finding private money to expand the Allen array has proven difficult, but he said SETI now has an application in with the National Science Foundation to help with the construction and operation. "At the beginning, there were maybe four or five people in the room when we'd call a meeting to discuss SETI," Drake said. "It was definitely on the fringe."

"Now SETI and the field of astrobiology are mainstream, and a meeting might bring in 1,000 people," he said. "I never, never could have imagined that when I started."

Tuesday, December 22, 2009

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

Earth-Like Planet Nearby

Scientists spot nearby 'super-Earth'

By John D. Sutter, CNN

December 16, 2009 5:12 p.m. EST

(CNN) -- Astronomers announced this week they found a water-rich and relatively nearby planet that's similar in size to Earth.

While the planet probably has too thick of an atmosphere and is too hot to support life similar to that found on Earth, the discovery is being heralded as a major breakthrough in humanity's search for life on other planets.

"The big excitement is that we have found a watery world orbiting a very nearby and very small star," said David Charbonneau, a Harvard professor of astronomy and lead author of an article on the discovery, which appeared this week in the journal Nature.

The planet, named GJ 1214b, is 2.7 times as large as Earth and orbits a star much smaller and less luminous than our sun. That's significant, Charbonneau said, because for many years, astronomers assumed that planets only would be found orbiting stars that are similar in size to the sun.

Because of that assumption, researchers didn't spend much time looking for planets circling small stars, he said. The discovery of this "watery world" helps debunk the notion that Earth-like planets could form only in conditions similar to those in our solar system.

"Nature is just far more inventive in making planets than we were imagining," he said.

In a way, the newly discovered planet was sitting right in front of astronomers' faces, just waiting for them to look. Instead of using high-powered telescopes attached to satellites, they spotted the planet using an amateur-sized, 16-inch telescope on the ground.

There were no technological reasons the discovery couldn't have happened long ago, Charbonneau said.

The planet is also rather near to our solar system -- only about 40 light-years away.

Planet GJ 1214b is classified as a "super-Earth" because it is between one and 10 times as large as Earth. Scientists have known about the existence of super-Earths for only a couple of years. Most planets discovered by astronomers have been gassy giants that are much more similar to Jupiter than to Earth.

Charbonneau said it's unlikely that any life on the newly discovered planet would be similar to life on Earth, but he didn't discount the idea entirely.

"This planet probably does have liquid water," he said.

By John D. Sutter, CNN

December 16, 2009 5:12 p.m. EST

(CNN) -- Astronomers announced this week they found a water-rich and relatively nearby planet that's similar in size to Earth.

While the planet probably has too thick of an atmosphere and is too hot to support life similar to that found on Earth, the discovery is being heralded as a major breakthrough in humanity's search for life on other planets.

"The big excitement is that we have found a watery world orbiting a very nearby and very small star," said David Charbonneau, a Harvard professor of astronomy and lead author of an article on the discovery, which appeared this week in the journal Nature.

The planet, named GJ 1214b, is 2.7 times as large as Earth and orbits a star much smaller and less luminous than our sun. That's significant, Charbonneau said, because for many years, astronomers assumed that planets only would be found orbiting stars that are similar in size to the sun.

Because of that assumption, researchers didn't spend much time looking for planets circling small stars, he said. The discovery of this "watery world" helps debunk the notion that Earth-like planets could form only in conditions similar to those in our solar system.

"Nature is just far more inventive in making planets than we were imagining," he said.

In a way, the newly discovered planet was sitting right in front of astronomers' faces, just waiting for them to look. Instead of using high-powered telescopes attached to satellites, they spotted the planet using an amateur-sized, 16-inch telescope on the ground.

There were no technological reasons the discovery couldn't have happened long ago, Charbonneau said.

The planet is also rather near to our solar system -- only about 40 light-years away.

Planet GJ 1214b is classified as a "super-Earth" because it is between one and 10 times as large as Earth. Scientists have known about the existence of super-Earths for only a couple of years. Most planets discovered by astronomers have been gassy giants that are much more similar to Jupiter than to Earth.

Charbonneau said it's unlikely that any life on the newly discovered planet would be similar to life on Earth, but he didn't discount the idea entirely.

"This planet probably does have liquid water," he said.

Tuesday, December 8, 2009

New Theory on Large Black Holes

Do Big Stars Spawn Giant Black Holes?

By Clara Moskowitz

,

Space.com

(Dec. 8, 2009) -- The biggest black holes in the universe are also the most perplexing. Scientists have long been confused about just how the earliest, most massive black holes formed, but new evidence now suggests they could have originated inside giant cocoon-like stars.

This idea is at odds with the prevailing thinking that large black holes are created by the clumping together of smaller black holes.

A University of Colorado scientists says the universe's biggest black holes may have been created by massive stars that formed soon after the Big Bang.

Not so, says University of Colorado at Boulder astrophysicist Mitchell Begelman. Rather, these behemoth black holes likely formed in the middle of even larger supermassive stars that could have held tens of millions of times the mass of our sun, according to Begelman.

"Until recently, the thinking by many has been that supermassive black holes got their start from the merging of numerous, small black holes in the universe," Begelman said. "This new model of black hole development indicates a possible alternate route to their formation."

Begelman studied how these gigantic stars could have formed, and how massive their cores might have been, to understand how they might have given rise to huge black holes. The results of his investigation will be published in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

The monster stars probably started forming within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang, which is thought to have created the universe around 14 billion years ago, Begelman found. When the cores of these giant stars had burned all their hydrogen, they would have collapsed, forming dense black holes. Meanwhile the outside gas layers of the stars remained as a shroud. Eventually, though, the black holes would have swallowed all the remaining stellar matter within their reach, ballooning rapidly to staggering weights, the study suggests.

This scenario could be more likely than the clumping process as the origin of supermassive black holes, Begelman said, though it's also possible that both methods have occurred.

"The problem that most people see in the clumping mechanism is whether you get these small black holes to merge frequently enough," Begelman told SPACE.com. "I'm working on trying to compare the rates of these two processes."

Over time, the resulting black boles might have merged with other giant black holes to form even larger leviathans.

"Big black holes formed via supermassive stars could have had a huge impact on the evolution of the universe, including galaxy formation," Begelman said.

Astronomers think most galaxies, including the Milky Way in which the Earth's solar system resides, have supermassive black holes at their centers. These black holes are probably responsible for a cosmic phenomenon called quasars, which are thought to occur when mass pours onto huge black holes, and some material is flung away in bright jets of high-energy radiation that can be seen across the universe.

By Clara Moskowitz

,

Space.com

(Dec. 8, 2009) -- The biggest black holes in the universe are also the most perplexing. Scientists have long been confused about just how the earliest, most massive black holes formed, but new evidence now suggests they could have originated inside giant cocoon-like stars.

This idea is at odds with the prevailing thinking that large black holes are created by the clumping together of smaller black holes.

A University of Colorado scientists says the universe's biggest black holes may have been created by massive stars that formed soon after the Big Bang.

Not so, says University of Colorado at Boulder astrophysicist Mitchell Begelman. Rather, these behemoth black holes likely formed in the middle of even larger supermassive stars that could have held tens of millions of times the mass of our sun, according to Begelman.

"Until recently, the thinking by many has been that supermassive black holes got their start from the merging of numerous, small black holes in the universe," Begelman said. "This new model of black hole development indicates a possible alternate route to their formation."

Begelman studied how these gigantic stars could have formed, and how massive their cores might have been, to understand how they might have given rise to huge black holes. The results of his investigation will be published in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society in London.

The monster stars probably started forming within the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang, which is thought to have created the universe around 14 billion years ago, Begelman found. When the cores of these giant stars had burned all their hydrogen, they would have collapsed, forming dense black holes. Meanwhile the outside gas layers of the stars remained as a shroud. Eventually, though, the black holes would have swallowed all the remaining stellar matter within their reach, ballooning rapidly to staggering weights, the study suggests.

This scenario could be more likely than the clumping process as the origin of supermassive black holes, Begelman said, though it's also possible that both methods have occurred.

"The problem that most people see in the clumping mechanism is whether you get these small black holes to merge frequently enough," Begelman told SPACE.com. "I'm working on trying to compare the rates of these two processes."

Over time, the resulting black boles might have merged with other giant black holes to form even larger leviathans.

"Big black holes formed via supermassive stars could have had a huge impact on the evolution of the universe, including galaxy formation," Begelman said.

Astronomers think most galaxies, including the Milky Way in which the Earth's solar system resides, have supermassive black holes at their centers. These black holes are probably responsible for a cosmic phenomenon called quasars, which are thought to occur when mass pours onto huge black holes, and some material is flung away in bright jets of high-energy radiation that can be seen across the universe.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

Theory on the Near Extinction of Humans

(Dec. 3) -- A massive volcanic eruption that occurred in the distant past killed off much of central India's forests and may have pushed humans to the brink of extinction, according to a new study that adds evidence to a controversial topic.

The Toba eruption, which took place on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia about 73,000 years ago, released an estimated 800 cubic kilometers of ash into the atmosphere that blanketed the skies and blocked out sunlight for six years. In the aftermath, global temperatures dropped by as much as 28 degrees Fahrenheit and life on Earth plunged deeper into an ice age that lasted around 1,800 years.

In 1998, Stanley Ambrose, an anthropology professor at the University of Illinois, proposed in the Journal of Human Evolution that the effects of the Toba eruption and the Ice Age that followed could explain the apparent bottleneck in human populations that geneticists believe occurred between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. The lack of genetic diversity among humans alive today suggests that during this time period humans came very close to becoming extinct.

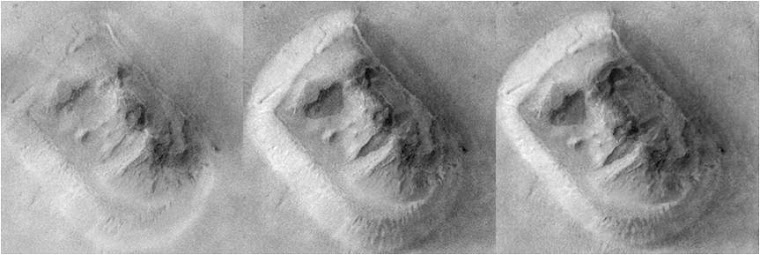

Satellite images show smoldering underground fires on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1997. A new study finds that a volcanic eruption on the same island 73,000 years ago had devastating effects on Earth.

To test his theory, Ambrose and his research team analyzed pollen from a marine core in the Bay of Bengal that had a layer of ash from the Toba eruption. The researchers also compared carbon isotope ratios in fossil soil taken from directly above and below the Toba ash in three locations in central India — some 3,000 miles from the volcano — to pinpoint the type of vegetation that existed at various locations and time periods.

Heavily forested regions leave carbon isotope fingerprints that are distinct from those of grasses or grassy woodlands.

The tests revealed a distinct change in the type of vegetation in India immediately after the Toba eruption. The researchers write in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology that their analysis indicates a shift to a "more open vegetation cover and reduced representation of ferns," which grow in humid conditions, all of which "would suggest significantly drier conditions in this region for at least 1,000 years after the Toba eruption."

The dryness probably also indicates a drop in temperature "because when you turn down the temperature you also turn down the rainfall," Ambrose said. "This is unambiguous evidence that Toba caused deforestation in the tropics for a long time."

He also concluded that the disaster may have forced the ancestors of modern humans to adopt new cooperative strategies for survival that eventually permitted them to replace Neanderthals and other archaic human species.

Although humans survived the event, researchers have detected increasing activity underneath a caldera at Yellowstone National Park, where some suspect another supervolcanic eruption will eventually take place. Though not expected to occur anytime soon, a Yellowstone eruption could coat half the United States in a layer of ash up to 3 feet deep.

The Toba eruption, which took place on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia about 73,000 years ago, released an estimated 800 cubic kilometers of ash into the atmosphere that blanketed the skies and blocked out sunlight for six years. In the aftermath, global temperatures dropped by as much as 28 degrees Fahrenheit and life on Earth plunged deeper into an ice age that lasted around 1,800 years.

In 1998, Stanley Ambrose, an anthropology professor at the University of Illinois, proposed in the Journal of Human Evolution that the effects of the Toba eruption and the Ice Age that followed could explain the apparent bottleneck in human populations that geneticists believe occurred between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. The lack of genetic diversity among humans alive today suggests that during this time period humans came very close to becoming extinct.

Satellite images show smoldering underground fires on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1997. A new study finds that a volcanic eruption on the same island 73,000 years ago had devastating effects on Earth.

To test his theory, Ambrose and his research team analyzed pollen from a marine core in the Bay of Bengal that had a layer of ash from the Toba eruption. The researchers also compared carbon isotope ratios in fossil soil taken from directly above and below the Toba ash in three locations in central India — some 3,000 miles from the volcano — to pinpoint the type of vegetation that existed at various locations and time periods.

Heavily forested regions leave carbon isotope fingerprints that are distinct from those of grasses or grassy woodlands.

The tests revealed a distinct change in the type of vegetation in India immediately after the Toba eruption. The researchers write in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology that their analysis indicates a shift to a "more open vegetation cover and reduced representation of ferns," which grow in humid conditions, all of which "would suggest significantly drier conditions in this region for at least 1,000 years after the Toba eruption."

The dryness probably also indicates a drop in temperature "because when you turn down the temperature you also turn down the rainfall," Ambrose said. "This is unambiguous evidence that Toba caused deforestation in the tropics for a long time."

He also concluded that the disaster may have forced the ancestors of modern humans to adopt new cooperative strategies for survival that eventually permitted them to replace Neanderthals and other archaic human species.

Although humans survived the event, researchers have detected increasing activity underneath a caldera at Yellowstone National Park, where some suspect another supervolcanic eruption will eventually take place. Though not expected to occur anytime soon, a Yellowstone eruption could coat half the United States in a layer of ash up to 3 feet deep.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

The Vatican Searches for Extraterrestrial Life

Vatican searches for aliens

Pope wants to learn the impact of extraterrestrial life on Caltholic Church

ARIEL DAVID

Associated Press Writer

Publication Date: 11/11/09

VATICAN CITY -- E.T. phone Rome.

Four hundred years after it locked up Galileo for challenging the view that the Earth was the center of the universe, the Vatican has called in experts to study the possibility of extraterrestrial alien life and its implication for the Catholic Church.

"The questions of life's origins and of whether life exists elsewhere in the universe are very suitable and deserve serious consideration," said the Rev. Jose Gabriel Funes, an astronomer and director of the Vatican Observatory.

Funes, a Jesuit priest, presented the results Tuesday of a five-day conference that gathered astronomers, physicists, biologists and other experts to discuss the budding field of astrobiology -- the study of the origin of life and its existence elsewhere in the cosmos.

Funes said the possibility of alien life raises "many philosophical and theological implications" but added that the gathering was mainly focused on the scientific perspective and how different disciplines can be used to explore the issue.

Chris Impey, an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona, said it was appropriate that the Vatican would host such a meeting.

"Both science and religion posit life as a special outcome of a vast and mostly inhospitable universe," he told a news conference Tuesday. "There is a rich middle ground for dialogue between the practitioners of astrobiology and those who seek to understand the meaning of our existence in a biological universe."

Thirty scientists, including non-Catholics, from the U.S., France, Britain, Switzerland, Italy and Chile attended the conference, called to explore among other issues "whether sentient life forms exist on other worlds."

Funes set the stage for the conference a year ago when he discussed the possibility of alien life in an interview given prominence in the Vatican's daily newspaper.

The Church of Rome's views have shifted radically through the centuries since Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake as a heretic in 1600 for speculating that other worlds could be inhabited.

Scientists have discovered hundreds of planets outside our solar system -- including 32 new ones announced recently by the European Space Agency. Impey said the discovery of alien life may be only a few years away.

"If biology is not unique to the Earth, or life elsewhere differs bio-chemically from our version, or we ever make contact with an intelligent species in the vastness of space, the implications for our self-image will be profound," he said.

This is not the first time the Vatican has explored the issue of extraterrestrials: In 2005, its observatory brought together top researchers for similar discussions.

In the interview last year, Funes told Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano that believing the universe may host aliens, even intelligent ones, does not contradict a faith in God.

"How can we rule out that life may have developed elsewhere?" Funes said in that interview.

"Just as there is a multitude of creatures on Earth, there could be other beings, even intelligent ones, created by God. This does not contradict our faith, because we cannot put limits on God's creative freedom."

Funes maintained that if intelligent beings were discovered, they would also be considered "part of creation."

The Roman Catholic Church's relationship with science has come a long way since Galileo was tried as a heretic in 1633 and forced to recant his finding that the Earth revolves around the sun. Church teaching at the time placed Earth at the center of the universe.

Today top clergy, including Funes, openly endorse scientific ideas like the Big Bang theory as a reasonable explanation for the creation of the universe. The theory says the universe began billions of years ago in the explosion of a single, super-dense point that contained all matter.

Earlier this year, the Vatican also sponsored a conference on evolution to mark the 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin's "The Origin of Species."

The event snubbed proponents of alternative theories, like creationism and intelligent design, which see a higher being rather than the undirected process of natural selection behind the evolution of species.

Still, there are divisions on the issues within the Catholic Church and within other religions, with some favoring creationism or intelligent design that could make it difficult to accept the concept of alien life.

Working with scientists to explore fundamental questions that are of interest to religion is in line with the teachings of Pope Benedict XVI, who has made strengthening the relationship between faith and reason a key aspect of his papacy.

Recent popes have been working to overcome the accusation that the church was hostile to science -- a reputation grounded in the Galileo affair.

In 1992, Pope John Paul II declared the ruling against the astronomer was an error resulting from "tragic mutual incomprehension."

The Vatican Museums opened an exhibit last month marking the 400th anniversary of Galileo's first celestial observations.

Tommaso Maccacaro, president of Italy's national institute of astrophysics, said at the exhibit's Oct. 13 opening that astronomy has had a major impact on the way we perceive ourselves.

"It was astronomical observations that let us understand that Earth (and man) don't have a privileged position or role in the universe," he said. "I ask myself what tools will we use in the next 400 years, and I ask what revolutions of understanding they'll bring about, like resolving the mystery of our apparent cosmic solitude."

The Vatican Observatory has also been at the forefront of efforts to bridge the gap between religion and science. Its scientist-clerics have generated top-notch research and its meteorite collection is considered one of the world's best.

The observatory, founded by Pope Leo XIII in 1891, is based in Castel Gandolfo, a lakeside town in the hills outside Rome where the pope has his summer residence. It also conducts research at an observatory at the University of Arizona, in Tucson.

------

On the Net:

Vatican Observatory, http://clavius.as.arizona.edu/vo

------

Associated Press writers Victor L. Simpson and Alessandra Rizzo contributed to this report

Pope wants to learn the impact of extraterrestrial life on Caltholic Church

ARIEL DAVID

Associated Press Writer

Publication Date: 11/11/09

VATICAN CITY -- E.T. phone Rome.

Four hundred years after it locked up Galileo for challenging the view that the Earth was the center of the universe, the Vatican has called in experts to study the possibility of extraterrestrial alien life and its implication for the Catholic Church.

"The questions of life's origins and of whether life exists elsewhere in the universe are very suitable and deserve serious consideration," said the Rev. Jose Gabriel Funes, an astronomer and director of the Vatican Observatory.

Funes, a Jesuit priest, presented the results Tuesday of a five-day conference that gathered astronomers, physicists, biologists and other experts to discuss the budding field of astrobiology -- the study of the origin of life and its existence elsewhere in the cosmos.

Funes said the possibility of alien life raises "many philosophical and theological implications" but added that the gathering was mainly focused on the scientific perspective and how different disciplines can be used to explore the issue.

Chris Impey, an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona, said it was appropriate that the Vatican would host such a meeting.

"Both science and religion posit life as a special outcome of a vast and mostly inhospitable universe," he told a news conference Tuesday. "There is a rich middle ground for dialogue between the practitioners of astrobiology and those who seek to understand the meaning of our existence in a biological universe."

Thirty scientists, including non-Catholics, from the U.S., France, Britain, Switzerland, Italy and Chile attended the conference, called to explore among other issues "whether sentient life forms exist on other worlds."

Funes set the stage for the conference a year ago when he discussed the possibility of alien life in an interview given prominence in the Vatican's daily newspaper.

The Church of Rome's views have shifted radically through the centuries since Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake as a heretic in 1600 for speculating that other worlds could be inhabited.

Scientists have discovered hundreds of planets outside our solar system -- including 32 new ones announced recently by the European Space Agency. Impey said the discovery of alien life may be only a few years away.

"If biology is not unique to the Earth, or life elsewhere differs bio-chemically from our version, or we ever make contact with an intelligent species in the vastness of space, the implications for our self-image will be profound," he said.

This is not the first time the Vatican has explored the issue of extraterrestrials: In 2005, its observatory brought together top researchers for similar discussions.

In the interview last year, Funes told Vatican newspaper L'Osservatore Romano that believing the universe may host aliens, even intelligent ones, does not contradict a faith in God.

"How can we rule out that life may have developed elsewhere?" Funes said in that interview.

"Just as there is a multitude of creatures on Earth, there could be other beings, even intelligent ones, created by God. This does not contradict our faith, because we cannot put limits on God's creative freedom."

Funes maintained that if intelligent beings were discovered, they would also be considered "part of creation."

The Roman Catholic Church's relationship with science has come a long way since Galileo was tried as a heretic in 1633 and forced to recant his finding that the Earth revolves around the sun. Church teaching at the time placed Earth at the center of the universe.

Today top clergy, including Funes, openly endorse scientific ideas like the Big Bang theory as a reasonable explanation for the creation of the universe. The theory says the universe began billions of years ago in the explosion of a single, super-dense point that contained all matter.

Earlier this year, the Vatican also sponsored a conference on evolution to mark the 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin's "The Origin of Species."

The event snubbed proponents of alternative theories, like creationism and intelligent design, which see a higher being rather than the undirected process of natural selection behind the evolution of species.

Still, there are divisions on the issues within the Catholic Church and within other religions, with some favoring creationism or intelligent design that could make it difficult to accept the concept of alien life.

Working with scientists to explore fundamental questions that are of interest to religion is in line with the teachings of Pope Benedict XVI, who has made strengthening the relationship between faith and reason a key aspect of his papacy.

Recent popes have been working to overcome the accusation that the church was hostile to science -- a reputation grounded in the Galileo affair.

In 1992, Pope John Paul II declared the ruling against the astronomer was an error resulting from "tragic mutual incomprehension."

The Vatican Museums opened an exhibit last month marking the 400th anniversary of Galileo's first celestial observations.

Tommaso Maccacaro, president of Italy's national institute of astrophysics, said at the exhibit's Oct. 13 opening that astronomy has had a major impact on the way we perceive ourselves.

"It was astronomical observations that let us understand that Earth (and man) don't have a privileged position or role in the universe," he said. "I ask myself what tools will we use in the next 400 years, and I ask what revolutions of understanding they'll bring about, like resolving the mystery of our apparent cosmic solitude."

The Vatican Observatory has also been at the forefront of efforts to bridge the gap between religion and science. Its scientist-clerics have generated top-notch research and its meteorite collection is considered one of the world's best.

The observatory, founded by Pope Leo XIII in 1891, is based in Castel Gandolfo, a lakeside town in the hills outside Rome where the pope has his summer residence. It also conducts research at an observatory at the University of Arizona, in Tucson.

------

On the Net:

Vatican Observatory, http://clavius.as.arizona.edu/vo

------

Associated Press writers Victor L. Simpson and Alessandra Rizzo contributed to this report

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

Maybe a meteor didn't kill the dinosaurs.

Time Magazine

Maybe an Asteroid Didn't Kill the Dinosaurs

By Jeffrey Kluger Monday, Apr. 27, 2009

When a scientific principle is common knowledge even in grammar schools, you know it's long since crossed the line from theory to established fact. That's the case with dinosaur extinction. Some 65 million years ago — as we've all come to know — an asteroid struck the Earth, sending up a cloud that blocked the sun and cooled the planet. That, in turn, wiped out the dinosaurs and made way for the rise of the mammals. The suddenness with which so many species vanished after the 65-million-year mark always suggested a single cataclysmic event, and the 1978 discovery of a 112-mi., 65-million-year-old crater off the Yucatán peninsula near the town of Chicxulub seemed to seal the deal.

Now, however, a new study in the Journal of the Geological Society throws all of that into question. The asteroid impact and the dinosaur extinction, argue the authors, may not have been simultaneous, but rather may have occurred 300,000 years apart. That's an eye-blink in geological time, but it's a relevant eye-blink all the same, one that occurred at just the right moment in ancient history to have sent the extinction theory entirely awry. (See pictures of meteors striking the earth.)

The controversial new paper was written by geoscientists Gerta Keller of Princeton University and Thierry Addate of the University of Lausanne, in Switzerland — and both researchers knew that challenging the impact doctrine would not be easy. The asteroid charged with killing the dinosaurs, after all, left more than the Chicxulub crater as its calling card. At the same 65-million-year depth, the geological record reveals that a thin layer of iridium was deposited pretty much everywhere in the world. Iridium is an element that's rare on Earth but common in asteroids, and a fine global dusting of the stuff is precisely what you'd expect to find if an asteroid struck the ground, vaporized on impact and eventually rained its remains back down. Below that iridium layer, the fossil record shows that a riot of species was thriving; above it, 65% of them went suddenly missing. (Read about China's dinosaur fossils.)

But Keller and Addate worried that we were misreading both the geological and fossil records. They conducted surveys at numerous sites in Mexico, particularly at a spot called El Peñón, very near the impact crater. They were especially interested in a 30-ft. layer of sediment just above the iridium layer. That sediment, they calculate, was laid down at a rate of about 0.8 in. to 1.2 in. per thousand years, meaning that the entire 30 feet took 300,000 years to settle into place. (See pictures of Mexico's swine flu outbreak.)

Analyzing the fossils at this small site, they counted 52 distinct species just below the iridium layer. Then they counted the species above it. The result: the same 52. It wasn't until they sampled 30 feet higher — and 300,000 years later — that they saw the die-offs.

"The mass extinction level can be seen above this interval," Keller says. "Not a single species went extinct as a result of the Chicxulub impact."

Keller's and Addate's species samplings are not, of course, conclusive, and plenty of other surveys since 1978 do tie the extinctions closely to the asteroid. But since the new digs were so close to ground zero, the immediate species loss ought to be have been — if anything — greater there than anywhere else in the world. Instead, the animals seemed to escape unharmed. Other paleontologists, however, believe that the very proximity of El Peñón to the impact site makes the results not more reliable, but less. Earthquakes and tsunamis that resulted from the collision could have wrought havoc on the sedimentary record, causing discrete strata to swirl together and completely scrambling timelines. Keller disagrees, pointing out that the slow accretion of sediment she and Addate recorded is completely inconsistent with a sudden event like a tsunami. (See pictures of animals in space.)

"The sandstone complex was not deposited over hours or days," she says. "Deposition occurred over a very long time period."

So if the Chicxulub asteroid didn't kill the dinosaurs, what did? Paleontologists have advanced all manner of other theories over the years, including the appearance of land bridges that allowed different species to migrate to different continents, bringing with them diseases to which native species hadn't developed immunity. Keller and Addate do not see any reason to stray so far from the prevailing model. Some kind of atmospheric haze might indeed have blocked the sun making the planet too cold for the dinosaurs — it just didn't have to have come from an asteroid. Rather, they say, the source might have been massive volcanos, such as the ones that blew in the Deccan Traps in what is now India at just the right point in history. (See pictures of the space race.)

For the dinosaurs that perished 65 million years back, extinction was extinction and the precise cause was immaterial. But for the bipedal mammals who were allowed to rise once the big lizards were finally gone, it is a matter of enduring fascination.

Maybe an Asteroid Didn't Kill the Dinosaurs

By Jeffrey Kluger Monday, Apr. 27, 2009

When a scientific principle is common knowledge even in grammar schools, you know it's long since crossed the line from theory to established fact. That's the case with dinosaur extinction. Some 65 million years ago — as we've all come to know — an asteroid struck the Earth, sending up a cloud that blocked the sun and cooled the planet. That, in turn, wiped out the dinosaurs and made way for the rise of the mammals. The suddenness with which so many species vanished after the 65-million-year mark always suggested a single cataclysmic event, and the 1978 discovery of a 112-mi., 65-million-year-old crater off the Yucatán peninsula near the town of Chicxulub seemed to seal the deal.

Now, however, a new study in the Journal of the Geological Society throws all of that into question. The asteroid impact and the dinosaur extinction, argue the authors, may not have been simultaneous, but rather may have occurred 300,000 years apart. That's an eye-blink in geological time, but it's a relevant eye-blink all the same, one that occurred at just the right moment in ancient history to have sent the extinction theory entirely awry. (See pictures of meteors striking the earth.)

The controversial new paper was written by geoscientists Gerta Keller of Princeton University and Thierry Addate of the University of Lausanne, in Switzerland — and both researchers knew that challenging the impact doctrine would not be easy. The asteroid charged with killing the dinosaurs, after all, left more than the Chicxulub crater as its calling card. At the same 65-million-year depth, the geological record reveals that a thin layer of iridium was deposited pretty much everywhere in the world. Iridium is an element that's rare on Earth but common in asteroids, and a fine global dusting of the stuff is precisely what you'd expect to find if an asteroid struck the ground, vaporized on impact and eventually rained its remains back down. Below that iridium layer, the fossil record shows that a riot of species was thriving; above it, 65% of them went suddenly missing. (Read about China's dinosaur fossils.)

But Keller and Addate worried that we were misreading both the geological and fossil records. They conducted surveys at numerous sites in Mexico, particularly at a spot called El Peñón, very near the impact crater. They were especially interested in a 30-ft. layer of sediment just above the iridium layer. That sediment, they calculate, was laid down at a rate of about 0.8 in. to 1.2 in. per thousand years, meaning that the entire 30 feet took 300,000 years to settle into place. (See pictures of Mexico's swine flu outbreak.)

Analyzing the fossils at this small site, they counted 52 distinct species just below the iridium layer. Then they counted the species above it. The result: the same 52. It wasn't until they sampled 30 feet higher — and 300,000 years later — that they saw the die-offs.

"The mass extinction level can be seen above this interval," Keller says. "Not a single species went extinct as a result of the Chicxulub impact."

Keller's and Addate's species samplings are not, of course, conclusive, and plenty of other surveys since 1978 do tie the extinctions closely to the asteroid. But since the new digs were so close to ground zero, the immediate species loss ought to be have been — if anything — greater there than anywhere else in the world. Instead, the animals seemed to escape unharmed. Other paleontologists, however, believe that the very proximity of El Peñón to the impact site makes the results not more reliable, but less. Earthquakes and tsunamis that resulted from the collision could have wrought havoc on the sedimentary record, causing discrete strata to swirl together and completely scrambling timelines. Keller disagrees, pointing out that the slow accretion of sediment she and Addate recorded is completely inconsistent with a sudden event like a tsunami. (See pictures of animals in space.)

"The sandstone complex was not deposited over hours or days," she says. "Deposition occurred over a very long time period."

So if the Chicxulub asteroid didn't kill the dinosaurs, what did? Paleontologists have advanced all manner of other theories over the years, including the appearance of land bridges that allowed different species to migrate to different continents, bringing with them diseases to which native species hadn't developed immunity. Keller and Addate do not see any reason to stray so far from the prevailing model. Some kind of atmospheric haze might indeed have blocked the sun making the planet too cold for the dinosaurs — it just didn't have to have come from an asteroid. Rather, they say, the source might have been massive volcanos, such as the ones that blew in the Deccan Traps in what is now India at just the right point in history. (See pictures of the space race.)

For the dinosaurs that perished 65 million years back, extinction was extinction and the precise cause was immaterial. But for the bipedal mammals who were allowed to rise once the big lizards were finally gone, it is a matter of enduring fascination.

Monday, April 20, 2009

Man Not Alone In Universe

(CNN) -- Earth Day may fall later this week, but as far as former NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell and other UFO enthusiasts are concerned, the real story is happening elsewhere.

Former NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell, shown in 1998, says "there really is no doubt we are being visited."

Former NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell, shown in 1998, says "there really is no doubt we are being visited."

Mitchell, who was part of the 1971 Apollo 14 moon mission, asserted Monday that extraterrestrial life exists, and that the truth is being concealed by the U.S. and other governments.

He delivered his remarks during an appearance at the National Press Club following the conclusion of the fifth annual X-Conference, a meeting of UFO activists and researchers studying the possibility of alien life forms.

Mankind has long wondered if we're "alone in the universe. [But] only in our period do we really have evidence. No, we're not alone," Mitchell said.

"Our destiny, in my opinion, and we might as well get started with it, is [to] become a part of the planetary community. ... We should be ready to reach out beyond our planet and beyond our solar system to find out what is really going on out there."

Mitchell grew up in Roswell, New Mexico, which some UFO believers maintain was the site of a UFO crash in 1947. He said residents of his hometown "had been hushed and told not to talk about their experience by military authorities." They had been warned of "dire consequences" if they did so.

But, he claimed, they "didn't want to go to the grave with their story. They wanted to tell somebody reliable. And being a local boy and having been to the moon, they considered me reliable enough to whisper in my ear their particular story."

Roughly 10 years ago, Mitchell claimed, he was finally given an appointment at Pentagon to discuss what he had been told.

An unnamed admiral working for the Joint Chiefs of Staff promised to uncover the truth behind the Roswell story, Mitchell said. The stories of a UFO crash "were confirmed," but the admiral was then denied access when he "tried to get into the inner workings of that process."

The same admiral, Mitchell claimed, now denies the story.

"I urge those who are doubtful: Read the books, read the lore, start to understand what has really been going on. Because there really is no doubt we are being visited," he said.

"The universe that we live in is much more wondrous, exciting, complex and far-reaching than we were ever able to know up to this point in time."

A NASA spokesman denied any cover-up.

"NASA does not track UFOs. NASA is not involved in any sort of cover-up about alien life on this planet or anywhere else -- period," Michael Cabbage said Monday.

Debates have continued about what happened at Roswell. The U.S. Air Force said in 1994 that wreckage recovered there in 1947 was most likely from a balloon-launched classified government project.

Stephen Bassett, head of the Paradigm Research Group (PRG), which hosted the X-Conference, said that the truth about extraterrestrial life is being suppressed because it is politically explosive.

"There is a third rail [in American politics], and that is the UFO question. It is many magnitudes more radioactive than Social Security ever dreamed to be," Bassett said.

Former NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell, shown in 1998, says "there really is no doubt we are being visited."

Former NASA astronaut Edgar Mitchell, shown in 1998, says "there really is no doubt we are being visited."

Mitchell, who was part of the 1971 Apollo 14 moon mission, asserted Monday that extraterrestrial life exists, and that the truth is being concealed by the U.S. and other governments.

He delivered his remarks during an appearance at the National Press Club following the conclusion of the fifth annual X-Conference, a meeting of UFO activists and researchers studying the possibility of alien life forms.

Mankind has long wondered if we're "alone in the universe. [But] only in our period do we really have evidence. No, we're not alone," Mitchell said.

"Our destiny, in my opinion, and we might as well get started with it, is [to] become a part of the planetary community. ... We should be ready to reach out beyond our planet and beyond our solar system to find out what is really going on out there."

Mitchell grew up in Roswell, New Mexico, which some UFO believers maintain was the site of a UFO crash in 1947. He said residents of his hometown "had been hushed and told not to talk about their experience by military authorities." They had been warned of "dire consequences" if they did so.

But, he claimed, they "didn't want to go to the grave with their story. They wanted to tell somebody reliable. And being a local boy and having been to the moon, they considered me reliable enough to whisper in my ear their particular story."

Roughly 10 years ago, Mitchell claimed, he was finally given an appointment at Pentagon to discuss what he had been told.

An unnamed admiral working for the Joint Chiefs of Staff promised to uncover the truth behind the Roswell story, Mitchell said. The stories of a UFO crash "were confirmed," but the admiral was then denied access when he "tried to get into the inner workings of that process."

The same admiral, Mitchell claimed, now denies the story.

"I urge those who are doubtful: Read the books, read the lore, start to understand what has really been going on. Because there really is no doubt we are being visited," he said.

"The universe that we live in is much more wondrous, exciting, complex and far-reaching than we were ever able to know up to this point in time."

A NASA spokesman denied any cover-up.

"NASA does not track UFOs. NASA is not involved in any sort of cover-up about alien life on this planet or anywhere else -- period," Michael Cabbage said Monday.

Debates have continued about what happened at Roswell. The U.S. Air Force said in 1994 that wreckage recovered there in 1947 was most likely from a balloon-launched classified government project.

Stephen Bassett, head of the Paradigm Research Group (PRG), which hosted the X-Conference, said that the truth about extraterrestrial life is being suppressed because it is politically explosive.

"There is a third rail [in American politics], and that is the UFO question. It is many magnitudes more radioactive than Social Security ever dreamed to be," Bassett said.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

100 Billion Earth-Like Planets in Milky Way

Galaxy may be full of 'Earths,' alien lifeStory Highlights

Astronomer: There may be 100 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way

If any of them have liquid water, they are likely to have some type of life, he says

Analysis: Thousands of intelligent civilizations may have emerged in the Milky Way

NASA's Kepler mission to search for habitable planets in our corner of the galaxy

By A. Pawlowski

CNN

(CNN) -- As NASA prepares to hunt for Earth-like planets in our corner of the Milky Way galaxy, there's new buzz that "Star Trek's" vision of a universe full of life may not be that far-fetched.

Pointy-eared aliens traveling at light speed are staying firmly in science fiction, but scientists are offering fresh insights into the possible existence of inhabited worlds and intelligent civilizations in space.

There may be 100 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way, or one for every sun-type star in the galaxy, said Alan Boss, an astronomer with the Carnegie Institution and author of the new book "The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets."

He made the prediction based on the number of "super-Earths" -- planets several times the mass of the Earth, but smaller than gas giants like Jupiter -- discovered so far circling stars outside the solar system.

Boss said that if any of the billions of Earth-like worlds he believes exist in the Milky Way have liquid water, they are likely to be home to some type of life.

"Now that's not saying that they're all going to be crawling with intelligent human beings or even dinosaurs," he said.

"But I would suspect that the great majority of them at least will have some sort of primitive life, like bacteria or some of the multicellular creatures that populated our Earth for the first 3 billion years of its existence."

Other scientists are taking another approach: an analysis that suggests there could be hundreds, even thousands, of intelligent civilizations in the Milky Way.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland constructed a computer model to create a synthetic galaxy with billions of stars and planets. They then studied how life evolved under various conditions in this virtual world, using a supercomputer to crunch the results.

Galaxy Quest

• The Milky Way is believed to be more than 13 billion years old.

• It is just one of billions of galaxies in the universe.

• The Milky Way has a circumference of about 250,000-300,000 light years.

• It is about 100,000 light years in diameter.

• There are three types of galaxies: ellipticals, spirals and irregulars.

• The Milky Way is a large disk-shaped barred spiral galaxy. (A barred galaxy has a bar-shaped structure in its middle.)

Source: Space.com In a paper published recently in the International Journal of Astrobiology, the researchers concluded that based on what they saw, at least 361 intelligent civilizations have emerged in the Milky Way since its creation, and as many as 38,000 may have formed.

Duncan Forgan, a doctoral candidate at the university who led the study, said he was surprised by the hardiness of life on these other worlds.

"The computer model takes into account what we refer to as resetting or extinction events. The classic example is the asteroid impact that may have wiped out the dinosaurs," Forgan said.

"I half-expected these events to disallow the rise of intelligence, and yet civilizations seemed to flourish."

Forgan readily admits the results are an educated guess at best, since there are still many unanswered questions about how life formed on Earth and only limited information about the 330 "exoplanets" -- those circling sun-like stars outside the solar system -- discovered so far.

The first was confirmed in 1995 and the latest just this month when Europe's COROT space telescope spotted the smallest terrestrial exoplanet ever found. With a diameter less than twice the size of Earth, the planet orbits very close to its star and has temperatures up to 1,500° Celsius (more than 2,700° Fahrenheit), according to the European Space Agency. It may be rocky and covered in lava.

Hunt for habitable planets

NASA is hoping to find much more habitable worlds with the help of the upcoming Kepler mission. The spacecraft, set to be launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida next week, will search for Earth-size planets in our part of the galaxy.

Don't Miss

NASA.gov: Explore the Kepler mission

iReport.com: Stargazers unite! Share your view of the universe

Kepler contains a special telescope that will study 100,000 stars in the Cygnus-Lyra region of the Milky Way for more than three years. It will look for small dips in a star's brightness, which can mean an orbiting planet is passing in front it -- an event called a transit.

"It's akin to measuring a flea as it creeps across the headlight of an automobile at night," said Kepler project manager James Fanson during a during a NASA news conference.

The focus of the mission is finding planets in a star's habitable zone, an orbit that would ensure temperatures in which life could exist. Watch a NASA scientist explain the search for habitable planets »

Boss, who serves on the Kepler Science Council, said scientists should know by 2013 -- the end of Kepler's mission -- whether life in the universe could be widespread.

Finding intelligent life is a very different matter. For all the speculation about the possibility of other civilizations in the universe, the question remains: If the rise of life on Earth isn't unique and aliens are common, why haven't they shown up or contacted us? The contradiction was famously summed up by the physicist Enrico Fermi in 1950 in what became known as the Fermi paradox: "Where is everybody?"

The answer may be the vastness of time and space, scientists explained.

"Civilizations come and go," Boss said. "Chances are, if you do happen to find a planet which is going to have intelligent life, it's not going to be in [the same] phase of us. It may have formed a billion years ago, or maybe it's not going to form for another billion years."

Even if intelligent civilizations did exist at the same time, they probably would be be separated by tens of thousands of light years, Forgan said. If aliens have just switched on their transmitter to communicate, it could take us hundreds of centuries to receive their message, he added.

As for interstellar travel, the huge distances virtually rule out any extraterrestrial visitors. iReport.com: Share your view of the universe

To illustrate, Boss said the fastest rockets available to us right now are those being used in NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto. Even going at that rate of speed, it would take 100,000 years to get from Earth to the closest star outside the solar system, he added.

"So when you think about that, maybe we shouldn't be worried about having interstellar air raids any time soon," Boss said.

Astronomer: There may be 100 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way

If any of them have liquid water, they are likely to have some type of life, he says

Analysis: Thousands of intelligent civilizations may have emerged in the Milky Way

NASA's Kepler mission to search for habitable planets in our corner of the galaxy

By A. Pawlowski

CNN

(CNN) -- As NASA prepares to hunt for Earth-like planets in our corner of the Milky Way galaxy, there's new buzz that "Star Trek's" vision of a universe full of life may not be that far-fetched.

Pointy-eared aliens traveling at light speed are staying firmly in science fiction, but scientists are offering fresh insights into the possible existence of inhabited worlds and intelligent civilizations in space.

There may be 100 billion Earth-like planets in the Milky Way, or one for every sun-type star in the galaxy, said Alan Boss, an astronomer with the Carnegie Institution and author of the new book "The Crowded Universe: The Search for Living Planets."

He made the prediction based on the number of "super-Earths" -- planets several times the mass of the Earth, but smaller than gas giants like Jupiter -- discovered so far circling stars outside the solar system.

Boss said that if any of the billions of Earth-like worlds he believes exist in the Milky Way have liquid water, they are likely to be home to some type of life.

"Now that's not saying that they're all going to be crawling with intelligent human beings or even dinosaurs," he said.

"But I would suspect that the great majority of them at least will have some sort of primitive life, like bacteria or some of the multicellular creatures that populated our Earth for the first 3 billion years of its existence."

Other scientists are taking another approach: an analysis that suggests there could be hundreds, even thousands, of intelligent civilizations in the Milky Way.

Researchers at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland constructed a computer model to create a synthetic galaxy with billions of stars and planets. They then studied how life evolved under various conditions in this virtual world, using a supercomputer to crunch the results.

Galaxy Quest

• The Milky Way is believed to be more than 13 billion years old.

• It is just one of billions of galaxies in the universe.

• The Milky Way has a circumference of about 250,000-300,000 light years.

• It is about 100,000 light years in diameter.

• There are three types of galaxies: ellipticals, spirals and irregulars.

• The Milky Way is a large disk-shaped barred spiral galaxy. (A barred galaxy has a bar-shaped structure in its middle.)

Source: Space.com In a paper published recently in the International Journal of Astrobiology, the researchers concluded that based on what they saw, at least 361 intelligent civilizations have emerged in the Milky Way since its creation, and as many as 38,000 may have formed.

Duncan Forgan, a doctoral candidate at the university who led the study, said he was surprised by the hardiness of life on these other worlds.

"The computer model takes into account what we refer to as resetting or extinction events. The classic example is the asteroid impact that may have wiped out the dinosaurs," Forgan said.

"I half-expected these events to disallow the rise of intelligence, and yet civilizations seemed to flourish."

Forgan readily admits the results are an educated guess at best, since there are still many unanswered questions about how life formed on Earth and only limited information about the 330 "exoplanets" -- those circling sun-like stars outside the solar system -- discovered so far.

The first was confirmed in 1995 and the latest just this month when Europe's COROT space telescope spotted the smallest terrestrial exoplanet ever found. With a diameter less than twice the size of Earth, the planet orbits very close to its star and has temperatures up to 1,500° Celsius (more than 2,700° Fahrenheit), according to the European Space Agency. It may be rocky and covered in lava.

Hunt for habitable planets

NASA is hoping to find much more habitable worlds with the help of the upcoming Kepler mission. The spacecraft, set to be launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida next week, will search for Earth-size planets in our part of the galaxy.

Don't Miss

NASA.gov: Explore the Kepler mission

iReport.com: Stargazers unite! Share your view of the universe

Kepler contains a special telescope that will study 100,000 stars in the Cygnus-Lyra region of the Milky Way for more than three years. It will look for small dips in a star's brightness, which can mean an orbiting planet is passing in front it -- an event called a transit.

"It's akin to measuring a flea as it creeps across the headlight of an automobile at night," said Kepler project manager James Fanson during a during a NASA news conference.

The focus of the mission is finding planets in a star's habitable zone, an orbit that would ensure temperatures in which life could exist. Watch a NASA scientist explain the search for habitable planets »

Boss, who serves on the Kepler Science Council, said scientists should know by 2013 -- the end of Kepler's mission -- whether life in the universe could be widespread.

Finding intelligent life is a very different matter. For all the speculation about the possibility of other civilizations in the universe, the question remains: If the rise of life on Earth isn't unique and aliens are common, why haven't they shown up or contacted us? The contradiction was famously summed up by the physicist Enrico Fermi in 1950 in what became known as the Fermi paradox: "Where is everybody?"

The answer may be the vastness of time and space, scientists explained.

"Civilizations come and go," Boss said. "Chances are, if you do happen to find a planet which is going to have intelligent life, it's not going to be in [the same] phase of us. It may have formed a billion years ago, or maybe it's not going to form for another billion years."

Even if intelligent civilizations did exist at the same time, they probably would be be separated by tens of thousands of light years, Forgan said. If aliens have just switched on their transmitter to communicate, it could take us hundreds of centuries to receive their message, he added.

As for interstellar travel, the huge distances virtually rule out any extraterrestrial visitors. iReport.com: Share your view of the universe

To illustrate, Boss said the fastest rockets available to us right now are those being used in NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto. Even going at that rate of speed, it would take 100,000 years to get from Earth to the closest star outside the solar system, he added.

"So when you think about that, maybe we shouldn't be worried about having interstellar air raids any time soon," Boss said.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

Billions of Earths

BBC NEWS

Galaxy has 'billions of Earths'

There could be one hundred billion Earth-like planets in our galaxy, a US conference has heard.

Dr Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Science said many of these worlds could be inhabited by simple lifeforms.

He was speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Chicago.

So far, telescopes have been able to detect just over 300 planets outside our Solar System.

Very few of these would be capable of supporting life, however. Most are gas giants like our Jupiter; and many orbit so close to their parent stars that any microbes would have to survive roasting temperatures.

But, based on the limited numbers of planets found so far, Dr Boss has estimated that each Sun-like star has on average one "Earth-like" planet.

This simple calculation means there would be huge numbers capable of supporting life.

"Not only are they probably habitable but they probably are also going to be inhabited," Dr Boss told BBC News. "But I think that most likely the nearby 'Earths' are going to be inhabited with things which are perhaps more common to what Earth was like three or four billion years ago." That means bacterial lifeforms.

Dr Boss estimates that Nasa's Kepler mission, due for launch in March, should begin finding some of these Earth-like planets within the next few years.

Recent work at Edinburgh University tried to quantify how many intelligent civilisations might be out there. The research suggested there could be thousands of them.

Story from BBC NEWS:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/science/nature/7891132.stm

Published: 2009/02/15 10:25:15 GMT

© BBC MMIX

Galaxy has 'billions of Earths'

There could be one hundred billion Earth-like planets in our galaxy, a US conference has heard.

Dr Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institution of Science said many of these worlds could be inhabited by simple lifeforms.

He was speaking at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Chicago.

So far, telescopes have been able to detect just over 300 planets outside our Solar System.

Very few of these would be capable of supporting life, however. Most are gas giants like our Jupiter; and many orbit so close to their parent stars that any microbes would have to survive roasting temperatures.

But, based on the limited numbers of planets found so far, Dr Boss has estimated that each Sun-like star has on average one "Earth-like" planet.

This simple calculation means there would be huge numbers capable of supporting life.

"Not only are they probably habitable but they probably are also going to be inhabited," Dr Boss told BBC News. "But I think that most likely the nearby 'Earths' are going to be inhabited with things which are perhaps more common to what Earth was like three or four billion years ago." That means bacterial lifeforms.

Dr Boss estimates that Nasa's Kepler mission, due for launch in March, should begin finding some of these Earth-like planets within the next few years.

Recent work at Edinburgh University tried to quantify how many intelligent civilisations might be out there. The research suggested there could be thousands of them.

Story from BBC NEWS:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/science/nature/7891132.stm

Published: 2009/02/15 10:25:15 GMT

© BBC MMIX

Wednesday, January 7, 2009

Runaway Stars

Astronomers Find New 'Runaway' Stars

By ANDREA THOMPSON

Space.com

LONG BEACH, Calif. (Jan. 7) — A total of 14 young stars racing through clouds of gas like bullets, creating brilliant arrowhead structures and tails of glowing gas, have been revealed by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. They represent a new type of runaway stars, scientists say.

The discovery of the speedy stars by Hubble, announced here today at the 213th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, came as something of a shock to the astronomers who found them.

"We think we have found a new class of bright, high-velocity stellar interlopers," said study leader Raghvendra Sahai of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Finding these stars is a complete surprise because we were not looking for them. When I first saw the images, I said 'Wow. This is like a bullet speeding through the interstellar medium.'"

The arrowhead structures, or bow shocks, seen in front of the stars are formed when the stars' powerful stellar winds (streams of neutral or charged gas that flow from the stars) slam into the surrounding dense gas, like a speeding boat pushing through water on a lake.

The strong stellar winds suggest that the stars are young, just a few million years old, the team concluded. Most stars produce powerful winds either when they are very young or very old; and only very massive stars (with masses greater than 10 times that of the sun) can keep generating these winds throughout their lifetimes.

But the objects Sahai and his team found aren't very massive, because they don't have glowing clouds of ionized gas around them. They appear to be medium-sized stars up to eight times more massive than the sun.

The stars' youth is also evidenced by the fact that the shapes of nebulas around dying stars are very different from what is seen around the stars found by Hubble, and old stars are almost never found near dense interstellar clouds, as these stars are.

Runaways

The bow shocks that the stars created in those interstellar clouds could be anywhere from 100 billion to a trillion miles wide (the equivalent of 17 times to 170 times the width of our solar system, out to the orbit of Neptune).

These bow shocks indicate that the stars are traveling fast, more than 112,000 mph (180,000 kph) with respect to the dense gas they're plowing through –- roughly five times faster than typical young stars.

Sahai and his team think the young stars are runaways that were jettisoned from the clusters they were born in.

"The high-speed stars were likely kicked out of their homes, which were probably massive star clusters," Sahai said.

There are two possible scenarios for how this stellar expulsion could have happened: One way is if one star in a binary system exploded as a supernova and the partner got kicked out. Another is a collision between two binary star systems or a binary system and a third star. One or more of these stars could have picked up energy from the interaction and escaped the cluster.

Assuming the youthful phase of the stars lasts only for a million years and that the stars are traveling at 112,000 mph, they have traveled about 160 light-years, Sahai said.

Tip of the Iceberg

The stars spotted by Sahai and his team aren't the first stellar runaways astronomers have found. The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) spied a few similar-looking objects in the late 1980s.

But those stars produced much larger bow shocks that the stars found by Hubble, suggesting they are more massive stars with more powerful stellar winds.